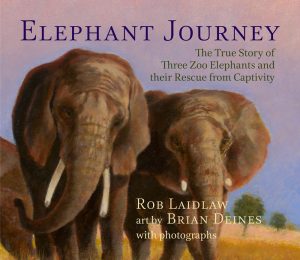

This is the second part of our interview with Rob Laidlaw, the author of Elephant Journey. Our discussion about the three Toronto Zoo elephants moves into the dangers currently faced by elephants in the wild, the current projects that Zoocheck, Rob’s not-for-profit, is working on, and a sneak preview at Rob’s next book with Pajama Press. Click here to read Part One.

–

S. It’s not just elephants in zoos that are in trouble. I read a recent New York Times article that said elephants in the wild are in danger of disappearing in the next ten years because of the ivory trade. Can you speak to that?

S. It’s not just elephants in zoos that are in trouble. I read a recent New York Times article that said elephants in the wild are in danger of disappearing in the next ten years because of the ivory trade. Can you speak to that?

R. I don’t know if ten years is an accurate prediction, but certainly if things continue to go the way they are now in Africa—because poaching for ivory is mainly centered in Africa—then future prospects for elephants look bleak. And it doesn’t matter whether they’re bush elephants or forest elephants, poaching for ivory is a threat to all of them. I believe the estimate is that 96-100 elephants are killed every day for ivory. One of the big problems is that it’s organized crime and militias in areas of civil conflict that are killing them in order to fund their initiatives. So it’s a very, very challenging thing to deal with. Certainly within ten years, if things continue to go as they are now, we’re going to see drastically fewer elephants in Africa. There’s about 400 thousand estimated to be in Africa today. In the past, there were several million and their populations were connected to each other throughout Africa, but today they’re in fragmented pockets that are separate from each other. I think we’ll soon see many of those fragments devoid of elephants. I doubt they’ll all be gone from the wild in ten years, but they may be restricted to a much smaller number of protected areas.

S. What efforts are in place or being established to help protect wild elephants?

R. There are all kinds of things, at the individual level, non-governmental organizational level, and at every political level from local to international. But it’s a huge, complicated web of problems to deal with. You have organized crime syndicates that see elephant tusks, rhino horn and other wildlife products as extremely lucrative and safer for them to profit from than drugs or weapons. They are extremely challenging to combat. If it were only one-off killings of elephants because of human-elephant conflict or even habitat fragmentation, it’s conceivable you could manage things like that. But organized crime syndicates and militias who obtain ivory and transport it to buyers in consumer nations through sophisticated smuggling networks are tremendously difficult to pin down. There are people, organizations and governments who are trying to address this issue, but it seems clear that far more official time, energy and resources must be allocated for intelligence gathering and for fighting this problem in a more coordinated and aggressive way. We also need additional boots on the ground protecting elephants wherever they live in the wild. And it should go without saying that the import and sale of ivory everywhere should be banned.

Ivory seized for destruction by U.S. law enforcement. Photo credit: Gavin Shire / USFWS USFWS ivory crush at Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge on November 14, 2013. Sourced via the Creative Commons.

S. That makes sense, and any trade in ivory should absolutely be banned. So, that same NYT article discussed how elephant conservation is the latest hot celebrity cause in Hollywood. Do you think that sort of media attention helps or hinders the push for elephant conservation?

R. I think it helps. Will it solve the problems? I don’t know. We’ve seen lots of celebrity support for all kinds of things, but while it does generate political and public awareness, it doesn’t always result in any resolution of the issue being discussed. But obviously the first step is letting people know. The theory is that with more people knowing about it, there will then be more pressure on governments to address the issue, because more people are bringing it to their attention. In real world politics, that’s not always the case. Sometimes it doesn’t matter what people think or what the facts are. For elephants however, I think a lot of people, including many politicians, are now listening. But even if they weren’t, the alternative is to do nothing, and that’s not acceptable. So even when things seem dire there may be that particular person, group of people, or political official who takes that message to heart and decide to make it their cause. Maybe then they’ll take it to a place where real change can occur.

S. What would you most like people to know about elephants?

R. I have friends who work with and care for a diversity of animal species. One of them operates a chimpanzee sanctuary, with more than a dozen of these enormously intelligent, complex sentient apes. At the sanctuary, they don’t actually call them animals. Instead, they refer to them as, “the people in the sanctuary….” They know them as individuals and understand that in many ways they are very much like us, so they see the chimps very differently than most people would. I think elephants are similar and are far more like us than most people imagine. They have almost the same life-span as humans, and enormous brains. They’re one of the most social animals in the world, possibly even more so than humans or orcas. Females spend their entire lives in the same family group, and they all have their own quirks, personalities, desires and needs. They develop friendships! It’s thought that some elephants will know two or three hundred other elephants during their lifetimes. They may recognize old friends that they haven’t seen in ten or fifteen years, when they get together in big congregations. They appear genuinely excited to see each other again, and no doubt they are. When you look at them on an individual basis, you see they really are very much like us. Except they’re elephants. It may sound silly but I really think more people should see them as elephant-people. If they saw them that way, maybe their perspective would change and, hopefully they’d then want better treatment for all elephants.

S. Before I started my internship here, I was thinking of sponsoring a baby elephant at an orphanage in Kenya. Can you recommend any reliable elephant-focused charities for someone who might want to help out?

R. The one you’re mentioning is the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and they’re known all around the world. Their program is very successful. They’ve introduced dozens of orphaned elephants back into the wild. They do the same thing with rhinos. If someone were interested in Indian elephants, there’s a group called Wildlife SOS that does fantastic work rescuing street elephants. They’re also trying to protect wild elephants and working elephants in timber camps. The Elephant Nature Park in northern Thailand that also does fantastic work helping elephants in need. And a colleague of mine has just started an elephant sanctuary in Brazil to rescue elephants in captivity there. Really, it’s just a matter of getting on the internet and finding something you’re interested in. There are many wonderful, effective elephant protection organizations.

Young orphan elephants at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya are herded by their keepers to the feeding and play area. Credit: Anita Ritenour, 2011, sourced via the Creative Commons.

S. You are also the founder of Zoocheck, a wildlife protection charity that works to protect the interests of wild animals globally. What are some of the initiatives Zoocheck is currently involved in?

R. Zoocheck always has a lot going on. As a campaigning wildlife protection organization, we’re involved in a broad range of investigative and legislative initiatives and litigations. Some of our efforts are focused on issues that affect large numbers of animals, but we also campaign to help individual animals in need as well. We’ve rescued monkeys, lemurs, big cats and, of course, elephants. We’re also trying to help Lucy, a Sri Lankan elephant that has lived at a zoo in Edmonton for almost her entire life. She’s in her early forties and all alone, and the zoo has dug in their heels about moving her. They want to keep her. We’re trying to get her out, but it’s been a long-term effort and we haven’t yet been successful. We’ve also been trying for a number of years to secure the release of a polar bear who has lived for more than two decades in a Mexican zoo, and we’re working to raise awareness about polar bears and other animals in Latin-American zoos. We also have an ongoing initiative to help animals in zoos in Ontario. We’ve worked across the country and internationally and have had tremendous success, but getting a law in place in Ontario has been a real challenge. The number of very poor zoos has dropped dramatically but there are still a number of them out there. Zoocheck also helps wildlife in the wild through a range of activities, such as funding aerial anti-poaching patrols in Africa, fighting organized culling of waterbirds in parks and reserves and campaigning to protect wild horses in western Canada. One initiative that is generating a lot of attention recently is the creation of the first cold-water sea pen sanctuary for belugas and killer whales in the world. We are part of an international collective of scientists, organizations and others who are trying to make that happen.

S. Oh, that’s cool!

R. We’re working on scoping out the possibilities in Canada. There are a number of sanctuaries that can accommodate dolphins from temperate or tropical climates, but nowhere yet for cold water dolphin and whale species. Hopefully, there will be soon.

S. That’s great; I know the documentary Blackfish got a lot of attention.

R. Some of the Blackfish people are involved in this initiative.

S. Whales and other large sea mammals are also animals that don’t do well in captivity. It’s good to know there are initiatives trying to find better ways to keep them safe. Speaking of, I guess it was last week that the story broke about the silverback gorilla….

R. Right. Harambe.

S. Yes. It’s an awful story, but do you have any thoughts on it?

R. Well, you know… it’s hard to second-guess the actions of the zoo staff. I have no doubt they didn’t want to kill Harambe, but felt they had to. Having said that, in the video footage I saw it looked like Harmabe was behaving naturally, like a silverback should. It didn’t look like he was being aggressive. But I understand there were about ten minutes of the incident that were not recorded on video, so I don’t know what happened during that time. Regardless, I think it’s inevitable that the animal will be killed in a situation like that, if it poses an immediate lethal threat, whether real or perceived, to a child. It doesn’t matter if it’s a tapir, elephant, gorilla, whatever… if a child gets into a cage with a potentially dangerous animal, there’s a good chance the animal will die. So Harambe’s killing was not a surprise to me. But what was surprising is that afterward, so many people, including many in the media, were asking, “why was that gorilla there in the first place, what’s the purpose?”

S. Oh!

R. Of course this was a tragedy but, if there’s anything positive about it, it’s the fact that people are now asking and trying to answer some bigger questions: What on earth was a gorilla doing in Cincinnati? What purpose does that serve, and how does being in captivity impact that animal’s life? There are many important discussions going on; all you have to do is search them out on Google. I think Harambe’s death will prove to be one of those watershed moments that help move the agenda for animals in captivity, and perhaps other animals as well, forward to a more progressive place. Ten or fifteen years ago, these kinds of discussions were exceedingly rare. But now they seem to be relatively common. Harambe’s death, the killing and public dissection of Marius the giraffe in Denmark, and the release of documentary films like Blackfish and The Cove—they are all watershed moments that generate discussion and make people rethink their positions. For animals, that is a very good thing.

Memorial in honour of Harambe at the Cincinnati Zoo. Photo credit: Kyle McCarthy on Flickr, 2016, sourced via the Creative Commons.

S. I hadn’t seen that layer growing out of the story, but I’m glad to know it’s happening. It’s the discussion that should be happening.

R. It’s occurring at a level that far exceeds anything I ever thought would happen.

S. That’s good. Last question: Can you give us any hints about your next project with Pajama Press?

R. Well, I’ve always been interested in bats because exploring caves is something I’ve done for the last 15 years or so. When I’m in caves, I encounter bats, and they’re fascinating animals. They’re small, but some of them live 30 or 40 years, making them very different from other creatures of a similar size. Bats are very intelligent and have great memories. One of the things that fascinated me is: I’d often be in the back of a cave, maybe ten or twelve hours from the entrance. To get there would require hundreds of turns and squeezes, but bats fly right to the backs of these caves using their echolocation. I asked a bat biologist, “how on earth do they do that?” and he said: “well, they remember, just like we do.” They’re utterly fascinating, and today bats are facing a lot of threats. The biggest one is disease, but they’re still persecuted in various parts of the world. There’s a need for a book that isn’t just about bat biology and behaviour, but about the realities that bats are facing today. Most of my books are advocacy tools. I’m interested in their potential to educate people and to help the animals. That’s what this one is about too. I want it to help bats.

–

If you missed the first part of this interview, you can find it here, or download both parts in .pdf format here. You can learn more about Rob’s efforts to rescue the three Toronto Zoo elephants and get them relocated to the PAWS Sanctuary in Elephant Journey, which can be found at an independent book store near you, or at a major retailer.

Resources Mentioned:

Zoocheck — Save Lucy – Save Yupi – Cormorants – Wild Horses

David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (Africa)

Global Sanctuary for Elephants (Brazil)

Elephant Nature Park (Thailand)

Wildlife SOS (India)

Learn Even More:

“How the Elephant Became the Newest Celebrity Cause” (NYT)

“The Killer in the Pool” (Blackfish)

Ric O’Barry’s Dolphin Project (The Cove)

Harambe the Silverback Gorilla (Huffington Post) (Toronto Star)

Marius the Giraffe (The Guardian) (NatGeo)

Arturo, the World’s Saddest Animal (The Daily Mail)