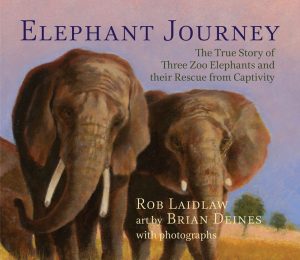

A few weeks ago I was fortunate enough to sit down with Rob Laidlaw, the author of Elephant Journey, when he stopped by our office. He answered some of my questions about the incredible true story of three elephants’ transfer from the Toronto Zoo, and we chatted more about the welfare of animals in captivity and some of the challenges they face.

–

S. Let’s start with your collaboration with our publisher, Gail Winskill, since you worked with her to produce Elephant Journey. What was it about the story of the three Toronto Zoo elephants that made it a good choice to adapt as a kids’ book?

S. Let’s start with your collaboration with our publisher, Gail Winskill, since you worked with her to produce Elephant Journey. What was it about the story of the three Toronto Zoo elephants that made it a good choice to adapt as a kids’ book?

R. I think there’s a number of different elements, one of them being that elephants are extremely popular animals. Everybody knows them; they’re charismatic mega-vertebrates that are extremely interesting animals when you look at them in a biological or behavioral sense. Not only that, it was a compelling story. This was the first time that I’m aware of that a city actually overrode an animal management decision of a major zoo and decided what was best for the animals. And of course, moving three elephants at any point in time to anywhere is a challenging task. A lot of different elements lent themselves to making it a compelling story for kids.

S. The book talks a lot about how the facilities in zoos aren’t adequate to support animals the size of elephants, especially because they can’t provide the space elephants need to keep them in shape. What about the elephants’ diets? Is that compromised in a zoo?

R. It can be. What you typically experience when you have animals in captivity, whether it’s elephants or naked mole rats, is a drastic alteration from what their natural diet would be to an artificial or formulated diet. In the wild an elephant or other large herbivore would be grazing on many species of plants, including grasses, bushes, flowers and trees, to name just a few. That provides them with diversity, not only in the nutritional value of the plants they eat, but it allows for a diversity of foraging behaviors. In captivity the diets for almost all animals are far simpler and more monotonous. What you see in elephants, particularly, is that their diets in captivity may not lend themselves to actually keeping their mouths and teeth healthy. And of course you get an almost complete absence of normal foraging behaviors because food is just given to them.

S. On the subject of exotic animals in zoos, would you consider the recent introduction of the giant pandas at the Toronto Zoo to be a success or a failure?

R. It depends on how you look at it. If you’re looking at it from the Zoo’s perspective, looking for a tourist attraction that will provide a short-term bump in attendance and revenues, then maybe you’d say it was a good idea. But when you look at the impact of bringing in very costly animals and how that might impact the animals that are already at the zoo, then I think you might reasonably say that it was probably not a good idea. All the resources that were put into accommodating the pandas, including millions of dollars in preparatory costs and ongoing costs while they’re here in Toronto, mean that those resources are not going to upgrades and repairs to enclosures for the animals that are already at the zoo. And in the big-picture scenario, when you’re looking at the conservation of endangered species, particularly pandas, I don’t believe having them in Toronto helps pandas in the wild in the slightest.

S. When I was researching that story I found there’s been a push by city counsellors to keep the twin panda cubs in Toronto longer. How do you feel about that?

R. I think it’s largely based on belief that they will continue to attract people to the zoo. Of course there are some people who see it as a point of pride for the city because the pandas were born here and they want to keep them. But from everything I know, it comes down to money. They believe these animals are going to generate an increased number of visitors and therefore increased revenue. It doesn’t usually work out like that, however. If you look at these panda loans over the long-term they’re often money-losing propositions.

S. Interesting…

R. In many zoos they’ve been extremely problematic and a massive burden on the facilities that have the animals. They’re not typically very good fundraisers. For the term of the loan, usually about five years, they’ll generate an increase in visitorship and revenues for the first two or three years, but then it drops off back to pretty much normal. Some zoos don’t even begin to recoup the costs associated with acquiring and displaying pandas.

S. Is there one zoo anywhere in the world that does a better job than most at respecting animals’ rights?

R. There are a few examples. There’s a small zoo started by the author Gerald Durrell several decades ago called the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. It’s a very small zoo on Jersey Island in the English Channel. They don’t have many of the big, charismatic animals that most zoos feel they need to attract visitors. What makes them really different however is that they allocate a substantial proportion of their budget towards legitimate in-situ conservation of wildlife. That means they work in these animals’ countries of origin on the politics of protecting animals and their habitats, so they have stable, ecologically-intact areas where they can release the surplus from their breeding efforts and where they can monitor them to ensure there’s a chance of survival. As well, there are all kinds of non-zoo facilities that people can visit to view animals in captivity, but they’re not traditional zoo environments. Take for example, where the Toronto Zoo elephants went, to the amazing PAWS Sanctuary in California. They’re not open every day but they do have open houses several times a year. There are other sanctuaries like that, where people can go and see a different form of captivity that’s far more benign in terms of its impact on animal welfare. In sanctuaries it’s often a more equitable type of relationship between us and the animals, and often any viewing that occurs is on the animals’ terms. If you look outside of the zoo arena at sanctuaries and specialist conservation centers, you can find all kinds of wonderful, innovative ideas on how to do things better.

Iringa and Toka at the PAWS Sanctuary in California.

S. I know I’ve seen places, probably in Kenya, where people can come have breakfast and there will be giraffes walking the grounds, or a hotel where elephants tend to walk through the lobby because that’s where they want to be at that time.

R. Throughout Africa there are a number of game reserves, they’re quite extensive in South Africa and a few other nations. Some of them will have animals that—on their own terms—will come and visit people. So you can encounter hippos, you can encounter elephants, and even some of the big cats. These reserves are very different from most captive settings because they are expansive, sometimes thousands of hectares in size, natural and the animals have the opportunity not to be seen if they don’t want to. They usually know they don’t have anything to fear from people, so they’re often moving about where they want. I believe that qualitatively the human experience of viewing animals in this kind of situation is orders of magnitude higher than seeing an animal in a cage, entirely removed from its ecological context.

S. How long did it take to get the three elephants transferred out of the Toronto Zoo and what was the most challenging part of that process?

R. The whole campaign to secure the release of the elephants took two and a half to three years. The reason for that was because the Zoo didn’t want to move the elephants where we wanted them to go. As well, a substantial number of external zoo supporters tried to stop it. It was a real challenge politically; in fact I think it was the most politicized thing we’ve ever been involved in. There were constant hurdles and delays, and it took time to address them all and to secure the release of the elephants. Right up until the elephants were driven out of the zoo on the trucks, people were trying to stop it.

S. From my understanding, now there are no elephants at the Toronto Zoo. Do you think they will ever try to acquire more?

R. No. I would be very surprised if they tried to obtain elephants again. There are not that many elephants out there. Approximately 300 elephants reside in North American zoos, and there are some in private hands as well. Importations from the wild are few and far between. Given what happened with the Toronto elephants, and the fact that their enclosure has already been refurbished, cost reasons alone would be an impediment to the Zoo getting elephants again. I think the days of northern zoos, with their relatively long winters, having elephant exhibits are gradually coming to a close.

S. That’s probably a good thing. Even before I encountered your book, or knew much at all about zoos or animals in captivity, it never sat well with me: that these animals that are native to hot climates have to sit through our winters.

R. It’s not that they can’t tolerate cool temperatures at all, because they can for short periods and there are things zoos can do to mitigate the weather concerns, at least partially. But when you get consistently cold weather over a period of weeks or months, it forces elephants and other warm-weather animals into indoor accommodations. That means they have even less space than they would in warmer weather when they can be outdoors, a less complex environment and therefore less physical and psychological stimulation. It’s compressing usually wide-ranging animals into ever-smaller conditions because of the cold that really exacerbates the problems they face from being in captivity in the first place.

S. Elephants are very smart and they have their own personalities, which is something the book makes very clear when it introduces Toka, Thika and Iringa. You got the chance to spend time with each of these elephants. Can you speak to what each of them was like in person?

R. Most of my direct exposure to them was on the trip down, because I was in the vehicle that followed the two trucks. What I saw were elephants that were just like other elephants I’ve seen. They seemed intelligent and inquisitive and they knew something was going on every time we stopped. When the doors were opened for feeding, watering and cleaning, they would extend their trunks out as far as they could. I assume they were trying to figure out what was going on. I think someone who had worked with them, or who had worked directly with other elephants, might notice a lot more than I would. But certainly you notice that when they’re looking at you, there’s somebody in there who’s intelligent and thinking. Of course moving any animal is a high-stress situation, so their normal behaviors and individual idiosyncrasies may not be as apparent in that situation, and certainly not to somebody like me who doesn’t know them well. From the sanctuary staff we now hear about their specific personality traits, like Thika’s curiousness, playfulness or boisterous behaviour. I’m sure the keepers at the zoo knew their moods, likes and dislikes, and now the sanctuary’s caretakers get to see them too, as well as how different they are from each other, just like people.

Thika enjoying a beautiful day at PAWS.

S. Was the trip to California stressful for you, or was it exciting because you knew the elephants were going somewhere better suited to them? What were your feelings?

R. I was just glad they were finally out of the zoo. It had been such a long campaign and we were tired of it. When they were finally on their way, there was a bit of a sense of relief. We’d overcome all the blockades that had been put in front of us. I have to admit, there was a little bit of stress during the move. When you’re moving any animals—but particularly large animals—the biggest fear is that they might collapse and go down. If that happens all kinds of physical problems can result, and in some cases, it can be just a matter of time before the animals are dead. We knew that the elephants had some health issues, particularly Iringa, but you never know how that will affect them during transport. Once they got to the sanctuary there were various benchmarks: surviving a week, then a month, then a year, because you never know. There are no guarantees that everything will work out fine. Issues can arise after the fact, animals can not only die in transport, they can also die afterwards because of the stress and trauma of it. But Toka, Thika and Iringa did well on the journey and arrived safely at PAWS.

–

Check out Part Two of our interview with Rob Laidlaw for more about elephants in the wild, and animal conservation efforts around the world. You can find your own copy of Elephant Journey at an independent book store near you, or at a major retailer to learn even more about Toka, Thika and Iringa.

Resources Mentioned:

Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust

PAWS Sanctuary and its Resident Elephants

Mfuwe Lodge in Zambia